Boat Propeller Accident Statistics / BARD Database: Historical Calls for Improving Completeness, Accuracy, and Ease of Use

Many have called for improving the completeness, accuracy, and ease of use of the records surrounding boat propeller accidents.

Those seeking to prevent or mitigate propeller accidents are generally forced to rely upon the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) Annual Boating Statistics report for propeller accident frequency data. For example, we covered the release of the 2011 Boating Statistics. We post propeller accident frequency data from the annual Boating Statistics reports from the last several years on our Propeller Accident Statistics page.

USCG recognizes not all accidents are reported in BARD, but claims almost all of the fatalities are reported. USCG claims the more serious the accident, the more likely it is to be reported. The boating industry says most propeller accidents are serious, USCG says the more serious the accident the more likely it is to be reported, so most propeller accidents are reported.

The individual accident reports behind USCG’s annual Boating Statistics report are themselves summarized in USCG’s annual Boating Accident Report Database (BARD).

When researchers are trying to determine the magnitude of a particular problem (such as boat propeller accidents), they first turn to USCG’s annual Boating Statistics report. Then to better understand the specifics of the individual accidents and if a particular device or process might have prevented or mitigated a particular accident, they turn to the individual accident reports in BARD.

The problems with that approach are:

- Many propeller accidents are not reported in BARD

- Many propeller accidents that are reported to USCG are not reported in BARD because they do not meet the specific criteria to be listed. Among the more commonly excluded one of interest to propeller accidents are commercial vessels (small commercial fishing boats or crabbing boats, government boats like state patrol boats, military boats), any accident involving a death in which a crime is being investigated, accidents on private lakes, and more. The 2011 annual summary specifically lists 19 reasons for not listing accidents in BARD. The 2011 annual summary notes 923 reported accidents (of all kinds) were excluded from BARD using those criteria.

- Some propeller accidents are reported in BARD, but not listed as propeller accidents.

- There have been longstanding issues with reporting boating accidents in National Parks. The National Park Service has its own internal reporting system and has often not reported those accidents in to USCG.

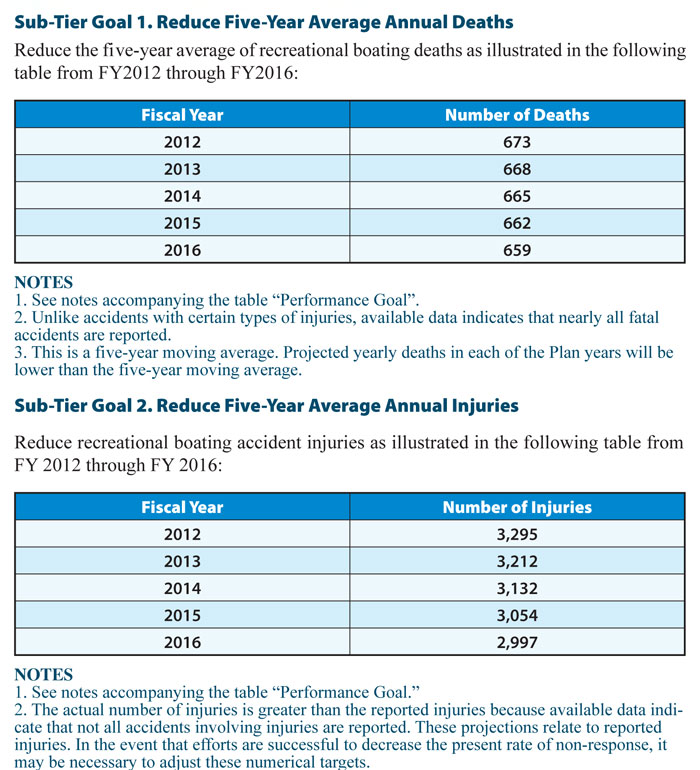

In addition, USCG has an incentive to not report accidents. The Office of Boating Safety is given annual targets for injuries and fatalities (see graphic below). If they can keep the total number of fatalities below those targets, USCG boating safety executives look good to their superiors. They can say, see, our boating safety programs are working, we came in under target. We are NOT saying USCG is trying to hide or eliminate accidents. But, you would have to be a fool to think they spend their spare time looking for unreported accidents when each one they find increases the annual accident counts and makes them look bad.

As you can see, there are considerable problems with the accident summary data counts (the problems we listed plus an incentive for USCG to NOT find unreported accidents).

To further complicate maters, the summary data that is reported has long been reported as a series of up to three events. For example, Event 1 struck floating object, Event 2 fell overboard, and Event 3 stuck by propeller. The annual summary data has long been reported in a manner in which researchers, the boating industry, reporters, and the general public see the Event 1 data (such as how many people were struck by a propeller as the very first event in the series of events of the accident) and think it represents the total number of people struck by propellers.

Once researchers begin to look in BARD at individual propeller accidents, more problems arise:

- Some propeller accidents are reported in BARD as propeller accidents but reported as the wrong boat type.

- There has been long standing confusion between “inboard” “inboard outboard” and “stern drive nomenclature. Meaning many accidents label stern drives as inboards.

- Many to most accidents are missing data from many of their data fields (incomplete accident reports).

- The early BARD data is very cryptic. Codes are used to represent entries forcing users to lookup the code for each data field to figure out what that particular entry in that specific data field means for that accident.

- Early (pre 1995) BARD grouped struck by boat accidents with struck by motor or propeller accidents. For some of those accidents researchers are able to use lookup codes in other data fields to determine if the person was struck by a boat or by the motor/propeller. For others, researchers are not able to distinguish being struck by a boat from being struck by the motor or propeller.

Over time there have certainly been some improvements made:

- BARD has become less cryptic and easier to use by professional researchers (still not easy to use by novices).

- Stuck by motor or propeller accidents have been isolated from struck by boat accidents.

- A struck by propeller field has been introduced.

- New data fields continue to be introduced (such as marine drive manufacturer and use of a kill switch) but those fields are rarely reported.

- USCG is now using a contractor to monitor news reports of boating accidents. If USCG does not receive a report on those accidents, they ask the state to follow up on them.

- USCG accepted with some modifications, a new table suggested by us and SPIN that more clearly distinguishes Event 1 accident data and the total number of accidents, however another confusing table remains in the annual Boating Statistics report.

- Implemented BARD-Web (online accident reporting system)

Even with these changes, the same basic problems remain: (1) Not all accidents are reported, (2) The annual summaries are confusing, and (3) The underlying data fields in BARD are often not completed.

Then to add insult to injury, in 2010 about half the states and territories chose to withhold their data from the Public version of BARD and thus we are now limited to seeing just over half of the individual accident reports. The others are hidden from our view as detailed in our USCG 2010 BARD Has Been Castrated post.

Before, we proceed, we note this post is in no way an attack on the U.S. Coast Guard. We appreciate the statistics they gather and recognize they are at the mercy of the states (only receive accidents if they are reported by the individual states). In addition, we recognize USCG’s ability to collect boat propeller accident data is limited by budgetary and manpower constraints.

We created this post to focus attention on the need to make sure boating accidents are reported, that they are reported accurately and completely, and that the resulting databases and publications are user friendly and open to boating safety professionals.

We will now list some of the historical calls for improving propeller accident data, several of them from the USCG itself.

Specific Calls For Improving Propeller Accident Data

“Struck by Propeller” Accidents 1978. USCG Policy Planning and Evaluation Staff. U.S. Coast Guard. 1979.

“It should be pointed out that these counts come only from the reported boating accidents. The true number of injuries caused by a propeller in 1978 is likely to be somewhere in the range between 855 and 3,420. This is because only about 10-20% of all injuries are reported in a given year. Chief, Accident Review Branch, does not feel that propeller accidents are over or under represented in the accidents currently being reported.”

Boat and Propeller Impact Injuries and Fatalities. Project 763584.20. Final Report. Edward Purcell and Walter Lincoln. U.S. Coast Guard Research and Development Center. Groton, CT. 1 March 1987.

“A review of the 1984 Coast Guard Boating Statistics listing fatalities resulting from being struck by a boat or propeller is contained in Appendix A. This review was conducted in April of 1985. There are 39 cases (42 fatalities) reviewed in Appendix A, and as noted, some of these were erroneously filed. In the official 1984 Boating Statistics Report there are only 8 fatalities ascribed to “struck by boat or propeller.” This is confusing and may be attributed to improper classifications such as “falls overboard” or “collision” as the primary cause of death. In any event, discrepancies of this magnitude make assessment very difficult.”

“The Coast Guard should gather its boating statistics by using an active random sampling technique, rather than relying on the passive voluntary collection of reports that is presently employed. The quality of the case reports listed in Appendix A varies from an official Coast Guard inquiry to the scribblings of an inebriated teenager. … NEISS has the correct approach to randomly sampling hospital data.”

Motorboat Propeller Injuries. Charles Price MD and Charles Moorefield MD. The Journal of the Florida Medical Association, Inc. June 1987. Vol.74. No.6.

from the Abstract: “Two hundred seven members of the Florida Orthopedic Society responded to a survey and identified 195 boat propeller injuries from 1979 to 1983. This number vastly exceeds the 30 cases reported to the U.S. Department of Transportation during the same five year period.”

from the article: “The purpose of this paper is to again call attention this problem, to point out that the true incidence of propeller injuries is much higher than reported ….”

Richard Snyder (Mercury Marine propeller accident expert) letter to James Getz (then chairman on the USCG National Boating Safety Advisory Council subcommittee on propeller guards) dated February 23, 1989.

“I informed Mr. Marmo (USCG) that I thought that people who were interested in fatalities in this category were not primarily concerned with how the victim got in the water but rather what was the real total of deaths caused by being struck.” (in reference to Event 1 propeller accident data Mr. Snyder had previously sent to Mr. Getz and incorrectly told Mr. Getz it represented the total number of propeller accidents.)

Recreational Boating Accident Statistical Methodologies. George Washington University study funded by a USCG grant. About 1992.

from the Executive Summary: “A recent study, prepared by the American Red Cross, indicates that only 3.2 percent of reported property damage accidents and 1.7 percent of reported non-fatal injury accidents are currently being reported to state authorities or the U.S. Coast Guard.”

from the Executive Summary: “After a thorough investigation of each data supplement alternative and completion of a comparison analysis, it was determined that the NEISS system would provide the best supplementary data for the U.S. Coast Guard boating accident database.”

A Study of Boat and Boat Propeller-Related Injuries in the United States. 1991-1992. Christine Branch-Dorsey, Suzanna Smith, and Denise Johnson of the Center for Disease Control (CDC). Final Report. June 1993. USCG and USDOT. Report No. CG-D-12-93.

“This study determined the feasibility and cost of obtaining a national sample and state-based supplemental data on boating injuries. Our adaptation of CPSC’s NEISS data base collected information on a wide range of industries by design and provided national estimates.”

The Study of Recreational Boating Safety by the National Transportation Safety Board and to Review the Coast Guard’s Boating Safety Programs. June 24, 1993. Recreational Boating Safety. 4.M.53:103-31. Subcommittee on the Coast Guard and Navigation of the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries. House of Representatives. 103rd Congress First Session. Serial No. 103-31.

Page 10: “Admiral Ecker: We publish annual statistics on boating accidents, as you might imagine, and we have a great deal of data there that is distributed quite widely to the boating administrators and other folks who have interest —

Mr. Tauzin: Admiral, I know we do. However, but I keep hearing and I read in both your testimonies that this data is terribly insufficient. If the purpose of reporting the data is to impress people, having data that is terribly insufficient is going to make a weaker impression.”

Page 24: Phil Keeter MRAA: “The Coast Guard reports that only a small fraction of the nonfatal boating accidents were reported to the Coast Guard or to local or State organizations; therefore, it cannot be assumed that accidents have occurred in proportion to those reported statistics. We believe, without adequate statistics, that it is questionable or even impossible to develop a national mandate for comprehensive changes to improve boating safety.”

Page 107: President of the National Water Safety Congress: “The accident statistics being reported are still flawed in that so many accidents are not reported. The statistics published by the Coast Guard can not be relied upon to give a true indication of what the problems really are. Therefore, it is difficult to effectively operate a boating safety program.

Prop Injury Statistics Incomplete. Soundings. Jim Flannery. July 1996.

“The propeller debate can bog down in statistics because no one is sure how many people are killed or injured in prop accidents.

Statistics are important because in any significant federal regulatory action costs and benefits of a rule must be weighed.”

“Marmo (USCG) says the Coast Guard hopes to get more complete data on propeller injuries through its Federal Register requests for information about prop injuries and wants to refine the reports it gets from the states to improve reporting on the severity of injuries “so we can make a better call as to the healthcare costs of the accidents”.

63rd NBSAC April 26-27, 1999. Portland, Oregon.

Page 21: “Lieutenant Belknap asked how many states were participating in the Boating Accident Report Database (BARD).

Captain Holmes said he didn’t know how many states, but that over 80 % of the reports are submitted electronically.

Mr. Vaca said that commercial accidents on sole state waters are not compiled. He also said that a previous concept on occupational boaters had merit.

Some discussion followed concerning recreational and commercial accidents, accident reporting, and the importance of having accurate accident data for use by the Coast Guard, states, industry and others.”

Inspector General of the United States. Audit of the Performance Measure of the Recreational Boating Safety Program. United States Coast Guard. Report Number: MA-2000-084 dated April 20, 2000.

“Database Used to Measure Progress Is Not Accurate. The data in the Boating Accident Report Database (BARD), which the Office of Boating Safety uses to collect statistical data from the States on recreational boating accidents have been consistently understated. BARD data were understated because recreational boating fatalities identified in the Coast Guard search and rescue management information system (SARMIS) were not reported to the Office of Boating Safety.”

We once had perhaps 20 more quotes here from about 1999-2012. However, we mistakenly deleted them. We may be able to recover some of them in the future and will post them at that time.

Houseboat Propeller Injury Avoidance Measures Proposed and Withdrawn by the U.S. Coast Guard: An Analysis by the Propeller Guard Information Center. Gary Polson P.E..June 10, 2010.

Page 162:

6. Improve propeller accident data collection and availability by:

A. Reformat USCGʼs annual Boating Statistics report to VERY CLEARLY distinguish between “Event 1” data and the total number of propeller fatalities and injuries (“All Event” data). See Appendix I.

B. USCG sign on with NEISS to begin collecting recreational boating propeller injury/ accident data as soon as possible (propeller injury data only, not all boating accidents).

C. USCG create an “official” houseboat propeller accident table similar to our Appendix D. This table is to be a “living document” with accidents added or updated as new information becomes available.

USCG 2010 Boating Accident Report Database (BARD) Has Been Castrated. Propeller Guard Information Center. July 8, 2011.

“We call for the boating industry, boating trade organizations, and the United States Coast Guard to encourage states to put the boating accident data back in the database if they truly want to protect their citizens. We have never heard of a single instance of identity theft based on data in USCG’s BARD public release database. The only thing left in there that looks very private to us is boat registration numbers and hull id numbers. We do not care if they leave out / redact the boat registration numbers or if they truncate the HIN AFTER the prefix.

If these states really wanted to protect their people they would leave their data in BARD so boating safety professionals had access to it …

Recreational Vessel Accident Reporting. Coast Guard. Docket No. USCG-2011-0674. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Federal Register. Vol.76. No.172. September 6, 2011. Pgs. 55079-55081.

USCG sought public comment on a two tier accident reporting system. The boat operator tells the state there was an accident, the state investigates it and fill out the form, or files the accident using BARD-web. The changes are being considered to reduce the problems when the operator fills our the form.

“Unfortunately, many accidents are not reported, or the information provided by boat owners or operators is often inaccurate or incomplete and frequently becomes available to the Coast Guard long after an accident occurs. Incomplete, inaccurate, or late accident information makes ensuring safe boating conditions more difficult, and may indicate that the accident reporting system could be improved.”

Its easy to see these problems (under reporting, incomplete reports, and BARD useability issues) have been around too long. While we are happy to see USCG asking for public input again in late 2011, it is very discouraging that the same problems are still around today that were around in 1978.

We encourage USCG to improve propeller accident data collection and availability by:

- Restoring data from the missing states claiming privacy issues in recent Public BARDs OR allow researchers access to that data. (About half the accident reports are missing in 2010 and 2011 Public BARD). Then making sure the same data for future years is similarly available.

- Reformatting their annual Boating Statistics report to VERY CLEARLY distinguish between “Event 1” data and the total number of propeller fatalities and injuries (“All Event” data).

- Signing on with NEISS to begin collecting recreational boating propeller injury/ accident data as soon as possible (propeller injury data only, not all boating accidents) and making that individual accident data available to researchers such as us.

- Implementing the two tier reporting system currently being discussed.