1989 National Boating Safety Advisory Council Propeller Guard Subcommittee Report

- Introduction to NBSAC Propeller Subcommittee Report

- The Actual Document – the 1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee Report

- References We Used

- Members of the Propeller Guard Subcommittee

- How NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards Functioned

- Adoption of the Final Report by the U.S. Coast Guard

- James E. Getz, Chairman of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards

- The “Public” Members

- Appendix E

- Current (mid 2010) Status of Members of the Subcommittee on Propeller Guards

- Some Shortcomings of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards Report

- Events at OMC Surrounding the 1989 Subcommittee on Propeller Guards Report

by Gary Polson – Initially published 30 July 2010

Introduction to our coverage of the NBSAC Propeller Subcommittee and their report

The National Boating Safety Advisory Council (NBSAC) is a committee of 21 people appointed to assist the U.S. Coast Guard on boating safety issues. It is composed of 21 people evenly split between these three groups:

- State Officials responsible for boating safety

- Boating Industry representatives

- Representatives of National Recreational Boating organizations AND the general public

NBSAC typically meets twice a year.

In 1988, in response to a number of propeller accidents, a NBSAC subcommittee was formed to investigate the feasibility of propeller guards. They issued a final report in 1989.

1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee Report is available online as part of an old U.S. Coast Guard docket (USCG 10299 Docket comment #146).

The National Boating Safety Advisory Subcommittee on Propeller Guards final report was strongly opposed to the use of propeller guards as seen in the quote below from page 24 of the report.

“Although the controversy which currently surrounds the issue of propeller guarding is, by its very nature, highly emotional and has attracted a great deal of publicity, there are no indications that there is a generic or universal solution currently available or foreseeable in the future. The boating public must not be misled into thinking there is a “safe” device which would eliminate or significantly reduce such injuries or fatalities.”

As soon as the report was released, the industry started touting it as a legal defense in propeller cases. Plaintiffs pointed out the subcommittee was stuffed with industry representatives and legal counsel, plus they explain how the report was written (described below).

The makeup of the Propeller Guard Subcommittee and methods used to construct the report were previously addressed in a 1990 deposition given by James E. Getz, Chairman of the Propeller Guard Subcommittee. Randall Edward Dacus vs. Harris-Kayot, Inc., Outboard Marine Corporation, and Horseshoe Bay Marina, Inc. District Court of Dallas County Texas. 101st Judicial District Court. No. 89-8181-E. James Getz’s deposition was taken 12 December 1990.

The deposition does an excellent job of describing the situation in James Getz own words, however, it is not widely available, and it is not very succinct (its a little wordy, sometimes jumps to other topics, and has some legalese in it).

Our investigation will focus on events leading up to formation of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards, members of the subcommittee, how James Getz said they arrived at their findings, how the industry has since used the study, how the study fits in with the Federal Preemption defense, and current status of members of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards.

Federal Preemption was the leading defense used by the industry from the mid 1990s up to loosing it in late 2002 in the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine. Under Federal Preemption, the industry claimed that since the U.S. Coast Guard did not require propeller guards on all boats in the 1971 Federal Boating Safety Act (FBSA), no state could require guards on any boat because they would preempt federal law.

The approximately 55 page 1989 NBSAC study was used by Getz as an expert witness for the industry to crush plaintiffs until the mid 1990’s when the Federal Preemption defense was perfected. In late 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Federal Preemption defense. Now (2010) the industry dusting off the 1989 study and relying more heavily upon the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards report once again.

Our analysis of the 1989 NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards will primarily rely on the following reference materials:

- The 1989 NBSAC Subcommittee Report

- James Getz’s 1990 deposition in Dacus vs. Harris-Kayot (full citation above)

- Decker vs. OMC transcript (Circuit Court of the 20th Judicial Circuit, Collier County, Florida. June 2009.

Our comments will be citing citing the above reference materials as:

- The Subcommittee on Propeller Guards report as R(x) where “x” is the page number in their report. Note we are talking about the page number printed on the page, not the Adobe pdf page number.

- Getz’s deposition by page number as G(x) where “‘x” is the page number in the deposition

- The Decker transcript will be cited as D(x) where “x” is the transcript page number

Members of the Propeller Guard Subcommittee

The National Boating Safety Advisory Council is composed of 21 members. Seven from each of three categories:

- State Officials responsible for boating safety

- Boating Industry representatives

- Representatives of National Recreational Boating organizations AND the general public

Members of the Propeller Guard Subcommittee were all members of NBSAC. The 1989 report identifies subcommittee members and the NBSAC group they represented on its title page (R title page) as:

- James E. Getz – Chairman, NBSAC State Member

- Donald J. Kerlin – USCG Representative

- Richard H. Lincoln – Industry Member

- WIlliam D. Selden – Public Member

- Herman T. VanMell – Public Member

While it looks like the committee is composed of a State Boating safety official, two public representatives, one industry member and a member of the Coast Guard, that was not exactly the case.

The subcommittee was originally formed in May 1988. At that time, (G29) its members were:

- James Getz – chairman – State Member

- Richard Lincoln – Industry Member

- Bill Fast – Public Member

- Don Kerlin (USCG)

About June 1988, Roy Montgomery (General Counsel for Mercury Marine) was added to the subcommittee) by the NBSAC Chairman after Getz requested some additional members be added to the subcommittee.(G29).

Herman VanMell and Lt. Joe Ruelas were also both appointed to the subcommittee at the same time as Roy Montgomery (June 1988) (G30). Getz said VanMell and Ruelas were added so the six people on the subcommittee equally represented the three categories of the council. The membership then became:

- Capt. James (Jim) E. Getz – state member – Chairman

- Lt. Joe L. Ruelas – state member BLA with marine patrol of Washington D.C. Metro Police

- Richard (Dick) H. Lincoln – industry member – OMC Director Public Relations (D2501)

- Roy T. Montgomery – industry member – Mercury Marine attorney

- William (Bill) M. Fast – public member – business agent for a local union in Seattle WA or Portland OR area (G35)

- Herman T. VanMell – public member (an attorney for Sunbeam prior to his retirement)(G32)

- Donald J. Kerlin – USCG

Getz said that upon learning of Roy Montgomery being appointed to the subcommittee, he voiced some concerns to the NSBSAC chairman “about what I perceived to be perceptions of his involvement in the subcommittee…. My concerns about Mr. Montgomery’s involvement revolved around the perception of people who might ultimately review our report, their perceptions of his involvement as tainting the final outcome of the subcommittee.” (G39).

Roy Montgomery was released from the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards after the last of the three regional informational gathering meetings, the one in Coeur D’Alene Idaho on May 12 & 13, 1989. (G40). He was a full member of the subcommittee for most of its duration. He just did not submit a written report at the end.

William Selden (public member) was added about the time of the meeting in New Bern North Carolina (14 November 1988) (G29 & R42). Selden filled the position vacated by Bill Fast who completed his term on the council and was no longer able to serve on the subcommittee. Bill Fast did not contribute to the final report.

The roster of members of the National Boating Safety Advisory Council Subcommittee on Propeller Guards then (after the last informational gathering meeting), became the final roster as published on the cover of the final report:

- James E. Getz – Chairman, NBSAC State Member

- Richard H. Lincoln – Industry Member

- William D. Selden – Public Member – retired from a Sporting Goods store in Richmond Virginia (G33)

- Herman T, VanMell – Public Member

- Donald J. Kerlin – USCG Representative

The final roster indicates the subcommittee was composed of one state member, one industry member, and two public members.

Getz said that after the addition of Montgomery, VanMell, and Ruelas, the subcommittee maintained a membership of six, equally divided between the three membership categories (industry, state members, public). (G30, G31).

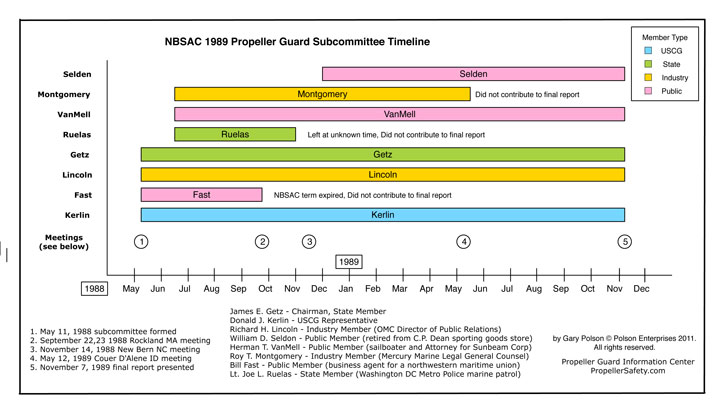

The comings and goings of NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards members can best be understood from the timeline below.

- May 1988 – Subcommittee Formed with Getz, Lincoln, Fast, Kerlin

- June 1988 – Montgomery, Fast, VanMell added

- September 1988 Rockland MA meeting

- November 1988 – Bern North Carolina Meeting: Fast leaves, Selden joins

- May 1989 – Coeur D’Alene Idaho Meeting (the last meeting): Montgomery leaves and is not replaced

- November 1989 – Final Report issued. Members are Getz, Lincoln, Seleden, VanMell, Kerlin

Although not part of the subcommittee, Robert Taylor, then managing engineer of Failure Analysis Associates (a firm often involved in testing products for legal firms) contributed an appendix to the final draft. Interestingly, Mr. Lincoln (with OMC) also presented a discussion of Robert Taylor’s graphs at the New Bern North Carolina meeting (Report Appendix D). Robert Taylor was an expert witness for OMC.

In November 2011 we prepared a timeline chart of the membership of the NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee. We have yet to re-verify all the data points, but went ahead and posted it with the Listman vs. OMC trial underway. We suspect the 1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard report will be discussed there.

Click on the image above to view a much larger PDF of the timeline.The NBSAC 1989 timeline chart above makes it much easier to follow the coming and going of its members and clearly illustrates the points each side of the propeller guard issue tries to make about the makeup and influences in the subcommittee. Also, please note Richard Snyder, Mercury Marine’s propeller guard expert witness, was also an active participant at most of those meetings.

How the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards Functioned

The entire process from creation to final report took approximately 18 months (G24). The final report was completed 7 November 1989 (G25).

A decision was made at the onset of the subcommittee that no minutes or transcripts would be kept of subcommittee discussions, opinions, and conclusions. Each member was to draft his own report, using the general format of the final report, and to explain how the subcommittee arrived at its conclusions and recommendations. (G22, G47, R1). Prior to the individual members writing their own rough drafts, a group discussion was held about the conclusions and opinions arrived at to that time (G21).

Getz then took the five individual rough drafts and combined them into a united draft (G20), sent it out to the subcommittee for comments, then he wrote the final report and had it typed up. The final report was endorsed by each member of the subcommittee. (G20).

Interestingly, no one asked who typed up the final report.

None of the individual rough drafts written by the subcommittee members were saved (G21). Getz says, “The general content of each report was the same.”(G21).

Per Getz, there was no disagreement among any members of the subcommittee as to any portion of the final report. They all agreed unanimously to the conclusions and recommendations (G61-G62). He said there was not even any significant disagreement among the rough drafts they submitted to him. (G62)

Getz explained the rough drafts were so similar because the group had already agreed upon their basic conclusions and recommendations (G62). When asked why he did not just go ahead and write the final report at that time (after reaching agreement and prior to members writing their own reports), he said the individual members had their own notes and he (Getz) may have missed an item what would have been good to have included in the final report (G63).

The only funding for the report was USCG funded travel to the meetings. The subcommittee met 4 times (R41-R43), then presented the final report:

- May 1988 NBSAC Meeting – the group was formed

- September 22-23 1988 Rockland Massachusetts at Boston Whaler’s facilities

- November 14 1988 NBSC Meeting New Bern North Carolina

- May 12-13 1989 NBSAC Meeting Couer d’ Alene Idaho

- November 1989 NBSAC Meeting – presented the final report

At the first NBSAC meeting, Getz invited people in the audience to sit in on the subcommittee meeting if they wished. “… the primary source of initial information came from Mr. Dick Snyder from Mercury Marine who was in attendance at the council meeting and who attended my subcommittee meeting.” (G52)

When asked if they made any special requests of OMC for propeller guarding information they might have, Getz said that prior to the first informational gathering meeting at Rockland Massachusetts (Sept 1988), “I probably made the request to Alexander Marcone to appear at our meeting in Rockland Massachusetts. … I believe Mr. Marcone, If I’m not mistaken, was on our initial contact list.”. Alexander Marcone was the in house attorney at OMC handling propeller accident litigation issues. (G53, G54). Note, Mr. Marcone’s name is sometimes spelled Marconi in records from that era.

The only individual accident reports the subcommittee looked at were some documents provided by Ben Hogan that Getz thought were tied to Dr. Lawrence Thibault’s analysis of marine accidents in Alabama. (G58, G59)

We assume the analysis referred to is that of Lawrence Thibault in his August 14, 1987 letter marked Re: Propeller Guarding sent to Stephen R. Bolding (an attorney). That letter in VERY abbreviated form describes the circumstances surrounding about 19 propeller accidents. Each description is accompanied by one or more sketches indicating how the person is thought to have entered the propeller. These few words and a sketch or two are vastly different from viewing the full accident reports (We are not saying they misconstrued what happened, we are saying they very significantly abbreviated what they think happened).

Getz said the information gathered seemed to be generally polarized to one end or the other (strongly in favor of, or strongly against the use of guards). (G61). Persons were advocating for one position or the other.

Adoption of the Final Report by the U.S. Coast Guard

Jim Getz presented the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards final report at the November 2009 NBSAC meeting. The report was adopted by NBSAC and later by the U.S. Coast Guard. That process is best described in the Ard v. Jensen propeller case court records (996 S.W.2d 594 (1999) Robert Leroy ARD, Appellant, v. James Donald JENSEN, Defendant, and The Brunswick Corporation, and Glastron, Inc., Respondents. No. WD 56041. Missouri Court of Appeals, Western District.):

“In 1988, the Coast Guard directed the National Boating Safety Advisory Council to consider whether the Coast Guard should implement federal requirements mandating the use of propeller guards. After hearings and research, the council recommended that “[t]he U.S. Coast Guard should take no regulatory action to require propeller guards.” National Boating Safety Advisory Council, Report of the Propeller Guard Subcommittee 24 (1989). The Coast Guard, through a letter written by Rear Admiral Robert T. Nelson, chief of the Office of Navigation, Safety and Waterway Services, to A. Newell Garden, chairman of the National Boating Safety Advisory Council, adopted the council’s recommendations concerning propeller guards. The letter said:

The regulatory process is very structured and stringent regarding justification. Available propeller guard accident data do not support imposition of a regulation requiring propeller guards on motorboats. Regulatory action is also limited by the many questions about whether a universally acceptable propeller guard is available or technically feasible in all modes of boat operation. Additionally, the question of retrofitting millions of boats would certainly be a major economic consideration. The Coast Guard will continue to collect and analyze data for changes and trends…. The Coast Guard will also review and retain any information made available regarding development and testing of new propeller guard devices or other information on the state of the art.”

Brunswick and Glastron contend that Nelson’s letter triggered federal preemption of the issue of propeller guards.

James E. Getz, Chairman of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards

Mr. Getz was appointed to chair the subcommittee. As mentioned earlier, immediately after the report was presented, he became a leading expert witness for the industry in propeller guard cases and continues to offer his services in that field today (mid 2010).

Its interesting that when the industry deposes plaintiff expert witnesses in propeller cases they often ask them if they are experts in biomechanics, experts in hydrodynamics, experts in naval architecture, experts in marine engineering, experts in safety engineering, experts in human factors, experts in the design of recreational boats, experts in warnings, experts in the state of the art of recreational boat equipment, if they have authored studies on emergency engine cut-off switches, if they have designed and built propeller guards, etc. While Mr. Getz who chaired the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards that resulted in the study they parade as the great authority on the issue lists his formal education as a B.S. in Education and a M.A. in Political Science from Eastern Illinois University.

The “Public” Members

William “Bill” M. Fast

William “Bill” M. Fast was said by Getz to have worked for a union and left the subcommittee about November 1988 when his term on NBSAC was running out.(G29, G35)

While preparing this report on the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards, we found some information we have never before seen concerning Mr. Fast. A little after the Getz 1990 deposition, Mr. Fast was indicted by a federal grand jury in Washington D.C. with 16 other former maritime union officials on federal charges of mail fraud. The charges stemmed from an investigation into allegations of embezzlement and rigging union elections. Mr. Fast had served as Port Commissioner from 1981-1989 and as a former rep of the Marine Engineer’s Beneficial Association/National Maritime Union.

The men were charged with misuse of union offices, manipulation of elections, enriching themselves at the union’s expense from Sept. 1984 through December 1991. The mail fraud counts from a referendum on a proposed union merger conducted through the mail in early 1988 (same time the subcommittee on propeller guards is being formed). They are accused of obtaining unmarked ballots, marking them, and substituting them for the mailed in ballots after discarding the real ones.

One of their defenses was the ballots they were accused of stealing through the mail were of little value, just the paper and ink used to print them.

References on legal problems of Mr. Fast and his alleged co-conspirators:

- Indicted for Mail Fraud. Seattle Times News Services. Seattle Times. 10 July 1993.

- Federal Jury Convicts 5 Maritime Union Officials of Embezeling. Moscow-Pullman Daily News. 7 July 1995.

- United States of America v. William M. Fast and several others. U.S. Court of Appeals. District of Columbia Circuit. 43 F.3d 707. Decided 13 January 1995. Rehearing denied 7 April 1995.)

- Union Official Pleads Guilty in Marine Engineers Beneficial Association Case. 16 December 1994. CRM (Criminal Division U.S. Dept. of Justice).

We found William M. Fast’s guilty plea and sentence in the PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) system under:

U.S. District Court

District of Columbia (Washington, DC)

CRIMINAL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 1:93-cr-00117-TPJ-11

Case title: USA v. DEFRIES, et al

Date Filed: 03/24/1993

Date Terminated: 05/20/1997

William M. Fast entered a guilty plea agreement on 20 May 1997 and was sentenced by Judge Thomas P. Jackson to 3rrs (Three Risk Reduction Sentences), One year unsupervised probation, fined $1,000.00, and ordered to pay a special assessment of $50.00. He was originally charged with (11) count(s). Count(s) 1-2, 1s, 2s, 6s, 7s, 8s-10s dismissed upon motion of government (as a trade for his plea agreement).

As a point of historical interest, we see Mr. William M. Fast on the phone with President Nixon in the White House Nixon tapes on 16 October 1972. He was a Branch Agent of District #1, Pacific Coast District of the National Marine Engineers Beneficial Association in Portland Oregon.

We also found a $1,000 contribution he made as Fast Consulting SCVC(Zipcode 97222) to Daniel Inouye in 1986 (contribution made 9 April 1985). He also gave a $1000 to the re-elect Packwood committee on 19 May 1985, $1000 to Senator Slade Gordon on 30 Oct 1986, and $5000 to Marine Engineers Beneficial Association Retirees Group Fund on 6 March 1984.

Herman T. Van Mell

Herman T. Van Mell was long time attorney for Sunbeam with a lifelong interest in sailing. It seems a bit odd to put a sailboater on a propeller guard study, plus his corporate legal background MAY have made him nonrepresentative of the typical boater.

In 1980, Sunbeam (a well known appliance firm) purchased Oster (a housewares firm). In 1981, Allegheny International (AI) (a conglomerate) purchased Sunbeam. AI went bankrupt in 1989 and Sunbeam emerged as Sumbeam-Oster Co., Inc.

Allegheny International was a large conglomerate like Brunswick.

On 2 August 1993, Roger Schipke was named as Chairman and CEO of Sunbeam-Oster. He served as an independent director on Brunswick Corporation’s Board of Directors from 1993-2007.

In 2002 Sunbeam once again emerged from Bankruptcy as American Household, Inc. (AHI) with a household division called Sunbeam Products. Jarden Corporation purchased AHI in 2004.

Herman Van Mell was participating in Chicago Yacht Club activities as early as 1946. We last see him in the news there about 1975. We found a November 2004 obituary for Herman T. Van Mell, a 93 year old retired Chicago corporate attorney and a nice history of Sunbeam on fundinguniverse.com.

William D. Selden

William D. Selden was one of five new members named to NBSAC in January 1989.

We found references to a William D. Seldon the fourth, fifth, and sixth. We think the William D. Selden on the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards was William D. Seldon IV (the fourth).

A William D. Selden of Richmond Virginia was Chief Commander of the U.S. Power Squadrons (USPS) in 1989. He was President of National Safe Boating Council in 2001, and previously served as a chairman of NBSAC.

We suspect Mr. Selden was actually representing one of the national boating organizations on NBSAC (USPS) in the joint category of organization and public members.

He, like Fast, also had a presidential connection. Mr Selden visited the White House 16 September 1989 and President Bush signed a proclamation honoring U.S. Power Squadrons.

William D. Selden IV (fourth) at C.P. Dean, won the Distinguished Retailer award from the Retail Merchants Association in 1987. He appears to have passed away about October 2003.

William D. Selden V (the fifth), a member of the class of 1970 at Hamden-Sydney College, appears to have recently been president of C.P. Dean Company a producer of billiards and game room supplies in Richmond Virginia. He is also, recently a past chair of the Retail Merchants Association (has members throughout northern Virginia).

A 1993 report says William D. Selden v (fifth) is the third generation of his family to run C.P. Dean.

We found a William D. Selden VI (the sixth) that was a member of the class of 1998 at Hampden-Sydney College.

The Selden family appears to be well connected, very civic minded, involved in government, and very active in boating safety. The only thing about them that makes us the slightest bit nervous about William D. Selden IV being on the subcommittee is their connection to billiards and bowling (both strong Brunswick segments).

Appendix E

Appendix E of the final report, Failure Analysis Associates Summary by Robert Taylor, reviewed the relative frequency of propeller fatalities vs. other boating fatalities, annual fatalities by other types of accidents, charted the risk of fatality when participating in various recreational activities, and the risk of propeller fatality by boat type. After the report was issued, Mr. Taylor became one of the primary expert witness used by industry in propeller accident cases.

Current (mid 2010) Status of Members of the Subcommittee on Propeller Guards

- James (Jim) E. Getz – state member – chairman of the subcommittee – currently works as an expert witness for International Marine Consulting Associates.

- Lt. Joe L. Ruelas – state member BLA with marine patrol of Washington D.C. Metro Police. We found what looks like he and his wife purchasing a home in Tacoma Park Maryland in May 2000. Zabasearch indicates he may still live in that house.

- Richard H. Lincoln – industry member / OMC – passed away June 2010 as a resident of Hilton Head Island South Carolina.

- Roy T. (Taylor) Montgomery – industry member – retired from Mercury Marine attorney – appears to still be in Fond du Lac.

- William (Bill) M. Fast – public member – union leader at that time – we see multiple William Fast’s living in Oregon, one was born in 1948 which would be about right for him.

- Herman T. VanMell – public member / Sunbeam attorney passed away 5 Sept. 2004 (In Memoriam. Harvard Law Bulletin. Spring 2005.)

- William D. Selden – Public Member – retired from running C.P. Dean a major Sporting Goods/Games manufacture in Richmond Virginia. Passed away about October 2003.

- Donald J. Kerlin – USCG currently still with USCG as Chief of the Program Management Branch of the Boating Safety Division.

Of the five people listed on the National Boating Safety Advisory Committee Subcommittee on Propeller Guards when the final report was generated, three are deceased, leaving only Jim Getz (chairman) and Donald Kerlin USCG representative. So the only person left alive that contributed to the final report according to Getz is Getz himself (it is our understanding that Donald Kerlin was on the committee to facilitate interaction with USCG, not to write a report).

Robert Taylor (author of Appendix E) continues to serve as an expert witness for the defense.

James Getz was contacted by ABYC/CED for possible input to the propeller guard test protocol being finalized in 2012.

Some Shortcomings of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards Report

We tried to just present the facts and not “pontificate” on several points surrounding the committee that appear to indicate the National Boating Safety Advisory Council Subcommittee on Propeller Guards was formed purely to further the industry’s talking points (agenda) for propeller guards and did so with Recommendation #1 on page 24 of their report, “The U.S. Coast Guard should take no regulatory action to require propeller guards.”

While still trying to just present the facts, we can not help but notice, their final report is as interesting for what was not in it was for what it contained. for what is in it. Several items are noticeable absent from the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards final report.

Totally absent from the report are:

- Any mention of guards not on the market at that time. We see a one word mention of patents in a review of their charges that was to be addressed by Roy Montgomery (Mercury attorney) at the New Berne North Carolina meeting (Report Appendix D). Mr. Montgomery was dropped from the subcommittee just before the writing of the final report and did not contribute to it.

- Any recognition of niche solutions (devices that prevent propeller accidents in certain applications or situations). The committee conducted the study as if a solution was not a solution unless it worked on all boats in all situations, as seen in this quote from page 22 of the Report: “No simple universal design suitable for all boats and motors In existence has been described or demonstrated to be technologically or economically feasible.” The subcommittee failed to acknowledge there were existing solutions for certain situations. For example conventional cage type guards on displacement houseboats do not create additional safety issues.

- Any electronic / sensor based propeller safety devices. The subcommittee’s charge (Report Appendix A) was limited to “some form of mechanical guard”. The use of sensors had been proposed years earlier at OMC (recorded in a 1986 group of legal exhibits by Don Kueny (Chief Engineer at OMC) as “Sensor Shut Off”. Kueny said the advantage of the Sensor Shutoff approach is there are no losses (no drag). The only disadvantage Kueny listed was “complicated”).

- Any mention of the “swing up” guard patented by Balius over a decade before the study (U.S. Patent 3,889,624). The entire guard swings up when underway and rides on small skis. It was a fore runner to the Flapper guard we proposed much latter. In addition to greatly reducing drag (guard rides up out of the water when underway as speed, Balius’s guard also removes the blunt trauma objection to being struck by guards at higher speeds (its up out of the way). The same 1986 Kueny legal exhibit mentioned above also listed “Retractable Ring or Guard” as an approach. Kueny said its advantage was “no losses” (no drag) and the only disadvantage listed was “complicated”. It wasn’t complicated, Balius worked it out long before then, plus our Flapper guard is even easier to build and retains much of the drag reduction advantages. The subcommittee made no mention of “swing up” or “Flapper” guard approaches.The Navigator 3PO guard built by Guy Taylor Jr. is another version of a “swing up” / “Flapper” guard. It is shown at above right.

- Any testing of propeller safety devices except a brief on water demo of a Chadwell guard. (Report Appendix D, Rockwell MA meeting). Even no testing of the Chadwell guard was performed. They just took those interested in riding aboard for a brief ride. The subcommittee accepted the industry’s stance that guards do not work and performed no testing on them.

- Any efforts to specifically “go down the list” addressing the subcommitte’s list charges in the final report. (Report Appendix A) (they failed to perform several tasks they were charged with.

- Any signatures of committee members except the chairman, Mr. Getz. Page 25 of the Report ends with a statement the report was “Unanimously adopted by the Propeller Guard Subcommittee” but only has the signature of Mr. Getz. The other members names are only typed.

- Continuity – some members were added after the fact finding sessions. Some with “institutional knowledge” of the committee’s efforts were dropped and did not participate in the final report:

- Ruelas – added after original formation and left before contributing to the final report

- Montgomery – added after original formation and left before contributing to the final report

- Fast – on the original committee, but left before contributing to the final report

- Selden – added at the last meeting to replace Montgomery

- Van Mell – added after original formation of the subcommittee

Excepting Mr Kerlin who was somewhat of a facilitator for USCG, a total of 7 people were on the subcommittee at one time or another. Of those 7 people, only 2 (Mr. Getz and Mr. Lincoln (OMC)) were on for the full stint.

- Any follow up on the Propeller Guard subcommittee’s recommendations (R24, R25) other that the first one which they tout, “The U.S. Coast Guard should take no regulatory action to require propeller guards.”

- We are a strong supporter of their second recommendation (improved accident reporting and involving NEISS (National Electronic Injury Surveillance System) data as an integral part of that data). Not only has nothing happened with NEISS, NEISS was not even mentioned in a 2 February 2009 USCG Propeller Accident Mitigation meeting examining additional sources of accident data titled, Beyond the BARD (Boating Accident Report Database). That meeting was led by David Marlow of Brunswick.

- We also support their 4th recommendation (developing meaningful warning labels and defining their most effective locations). Its now two decades later and the industry still does not have effective propeller safety warnings and

is still placing them in locations that cannot be read, or will not be seen in time to avoid being struck. Interestingly, David Marlow of Brunswick is also the point man on developing a propeller safety decal for the industry. In June 2002, USCG asked ABYC to develop a safety label to warn against propeller strikes. ABYC and BIRMC started working together on it. BIRMC is still working on trying to develop one compatible with current standards. (Reference pages 70-73 of Houseboat Propeller Injury Avoidance Measures Proposed and Withdrawn by the U.S. Coast Guard: An Analysis by the Propeller Guard Information Center). - We also support their 5th recommendation (reviewing manufacturing standards and emphasizing the importance of keeping passengers and operators in the boat – not letting them fall overboard). In July 2010 the industry was fighting against just that recommendation in the Regan vs. Starcraft Marine pontoon boat propeller injury case (U.S. District Court, Western District of Louisiana, Shreveport Division) in which the industry is arguing for applying the NMMA Certification standard to pontoon boat gate height and strength of pullout instead of the ABYC standard created years earlier and eventually adopted by NMMA. The shorter NMMA gate height allowed a passenger to fall over the gate and the low strength of the bolts in the hinges allowed him to rip out the gate, fall in, be ran over by the boat and struck the prop. ABYC said the gate should be 24 inches high and absorb 400 pounds of pull, but NMMA let them build at 19 inches with no strength requirement. The industry said they should be judged by the standards their trade organization chooses to accept, not by the ABYC standards, directly in opposition to the findings of the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards Report which they brandish with avengance.

Events at OMC Surrounding the 1989 Subcommitte on Propeller Guards Report

The NBSAC 1989 Subcommittee on Propeller Guards was just one of many major events surrounding propeller guarding issues. It can be better understood if viewed in perspective of what was going on at OMC and Mercury during that time frame, as well as some more recent events.

OMC was mounting a major offensive against propeller accident suits and teamed with Mercury to get them to help foot part of the bill. With a flury of cases in the wings, they were trying to put and end to propeller cases once and for all. They hoped to establish a series of courtroom wins that would raise the bar and protect them from being sued in the future.

Among their efforts and plans were:

- Project 441 – a project to investigate if it was possible to design a propeller guard that protected people with minimal performance losses. The project was approved in 1977. The device went on to be patented but OMC said it did caused too much drag and other problems to be used.

- Position Statement – somebody (thought to be their legal staff) put together a position statement on propeller guards. During the Decker case, they were unable to pin it down but it was prior to 1984, probably 1977 (D769).

- 1983 – Robert Taylor worked his first prop case for OMC (D2473).

- May 1988 the Propeller Guard Subcommittee was appointed.

- Mercury argued for Federal Preemption in a 7 August 1988 Lake Erie accident and the court agreed with them, as well as the U.S. Court of Appeals 8th District. (Boat Accident Reconstruction and Litigation. Second Edition. Hickman, Sampsel, van Hemmen. Pages 156-157.)

- By 1989 OMC had lined up two outside legal firms to help with propeller cases and related issues (Bowman and Brooke, and Snell and Wilmer)

- January 1989 Elliott v. Mercury Marine propeller guard case found in favor of Elliott. Mercury Marine ordered to pay $4.375 million, including $3 million in punitive damages in U.S. District Court of Northern District of Alabama

stemming from a July 1982 accident. - February/March 1989 OMC conducted a major full scale mock jury propeller trial that lasted several days.

- By 1989 Robert Taylor had a least ten prop guard cases going in which he was defending the manufacturer (D2497, D2498).

- Alex Marcone (often spelled Marconi) (OMC’s in-house counsel) got Robert Taylor (industry guard expert) on the National Boating Safety Advisory Council, then hired him to do the testing. (Reference Decker Case Blog Naples Daily News Thursday 18 June 2009 5:30 pm). Also see D2498, D2499. OMC had Getz call Taylor to come and give his presentation and OMC picked up the bill for his expenses.

- Taylor’s risk analysis was included as Appendix E of the 1989 report (R44-53). He compared the frequency and risk level of boating propeller injuries and fatalities to other activities per million hours of exposure.

- October 1989 James Pree files a prop guard suit against Brunswick as the result of a 1985 accident.

- November 1989 – the Propeller Guard Subcommittee Report was issued.

- Once the Propeller Subcommittee 1989 Report was released they quickly tried to keep it from being perceived as tainted from their and Mercury’s involvement, then tried establish to it as “the authority” on the prop guard issue. (Reference January 23, 1991 invoice from Snell and Wilmer to OMC and Reference G39,G40)

- As soon as the 1989 report was issued, Mr. Getz became a leading expert for the defense in propeller cases (G25, G26).

- June 1990 Elliott v. Mercury Marine (originally found $4.375 million for Elliott) was reversed by the U.S. Court of Appeals 11th Circuit.

- Create a database – By October 1990, Snell & Wilmer, OMC’s leading prop accident attorneys, were well underway at creating a large database of expert witnesses including their cv, prior depositions, legal materials, product literature, discovery materials, prop guard complaints, accident reports, and other matters relative to propeller guards. They created files for experts used by the other side and cross examination guides for each of them. Additionally, they created courtroom exhibits/displays.

- Create Prop Guard Reference Books – Snell & Wilmer created Prop Guard Refence Books that pulled together materials from their database.

- Regionize Prop Cases – They started training regional counsel to deal with prop matters geographically and supplied them with the database materials.

- Underwater Testing / Tyler A. Kress, David Porta, “MIke” Scott – OMC teamed with Mercury Marine to finance several underwater studies of guards striking cadaver body parts and anthropometric dummies.

- Injury Analysis of Impacts Between a Cage-Type Propeller Guard and a Submerged Head. “Mike” Scott and others. SAFE Journal 1994.

- Porta – “The Anatomical Consequences of Underwater Impacting Human Cadaver Legs with a Prop-Guarded Outboard Motor”.

- Kress’ Phd dissertation at the University of Tennessee, “Impact Biomechanics of the Human Body” included a segment titled, “Biomechanical Effectiveness of a Safety Device” A Boat Motor Cage-Type Propeller Guard”. It was published in 1996.

- A similar title, “An Underwater Impact Biomechanics Study to Evaluate a Boat Motor Cage-Type Propeller Guard as a Protective Device” was presented by Kress, Porta and two others at an International Conference on Biomechanics in Ireland in 1996.

- In 1991, OMC as able to get a Federal Court to eject the Shields case on Federal Preemption.

- In 1991, after winning the Shields case, OMC tried to have the Eggen vs Griffith case similarly thrown out on summary judgement using their Federal Preemption defense, but this time the Federal District Court did not agree.

- December 1991, Robert “Bob” Hooper applied for a patent on the Prop Buddy propeller guard. It was granted in January 1993. Prop Buddy was one of the earlier designs that allowed high speed boat operation with minimal drag and handling issues.

- By 1993, OMC was strongly chasing Federal Preemption as a defense.

- May 1998 Brunswick settled in Lewis v. Brunswick after oral arguments had been made in from of the U.S. Supreme Court propeller fatality case in order to retain the industry’s federal preemption defense.

- The industry lost their Federal Preemption defense in December 2002 with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Sprietsma vs. Mercury Marine prop case.

- In mid 2009 at the Decker case in Florida, Robert Taylor revealed his company had been paid about $60 million to defend the industry in propeller cases (D2475, D2476).

- June 2009 Decker v. OMC trial (D2505) talks about the 1989 Propeller Subcommittee being stacked with industry representatives to get the results they wanted.

“Although Outboard Marine Corporation has investigated and attempted to develop an efficient propeller guard for personal protection over the years and has examined and tested such claimed devices developed by others, no device which will protect the swimmer under some operational conditions without causing greater risk of injury under some other operational conditions is withing the state of the art of engineering design.”

Known to many as the SUNY (State University of New York) at Buffalo tests, these tests were conducted in a circular water track /tank (looks like a large donut from overhead) and were just about to get underway (actual test period was November 20, 1990- December 15, 1990). Analysis and reports continued for several years:

The mood just before the NBSAC Subcommittee on Propeller Guards released their report back in late 1989 is perhaps best summed up by a 27 March 1989 article in Crain’s Chicago Business News titled, “Brunswick, OMC Battle Prop Case”. In that article OMC and Brunswick are said to have battled prop suits for several years. Before this year (1989) boat makers were thought to have won or settled all but 2 of the several dozen cases. They lost a $1.1 million award in a 1985 OMC case and $4.5 million in a January 1989 jury award. Ben Hogan, plaintiff attorney, said he has been swamped with calls since the award. He presented evidenceU.S. Marines used a third party guard on small landing craft. OMC sent the marines a letter saying they would no longer warranty those engines, about two months ago the guards started to malfunction, tear loose and ruin the engines per the Marines who have since began taking them off. (Just a side note, there is currently some dispute over mechanical failure of some houseboat propeller guards several years ago in which it has been suggested those testing the guards intentionally pulled them apart.). Mercury has appealed the $4.5 million case. However, Mercury is currently working with the Marines on a guard for low speed applications per ROY MONTGOMERY vice president of law at Mercury Marine. Montgomery said, ” There clearly are low-speed applications where properly designed propeller guards can be useful.” The $4.5 million case involved a 14 year old girl struck at 5 mph. The final word on propeller guards may come this November when a U.S. Coast Guard advisory group that has been studying the issue for about a year recommends whether the government should require prop guards. “We’re anxiously awaiting the results” said Laurin Baker, OMC Director of Public Affairs.

UPDATE May 10, 2023

We recently published a four part manuscript on three early propeller guard reports. Volume II 1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee report is an in depth study of the 1989 NBSAC report and how it is the keystone of the boating industry’s legal defense in propeller guard product liability / product defect cases.

If you have any comments about our coverage of the study, or any knowledge of other interesting points surrounding it, please contact us.